Neulich hat mich Clive Thompson’s Linkfest-Newsletter zu einem schönen Artikel geführt, der sich mit »Googie-Architektur« beschäftigt – jenen US-amerikanischen Mid-Century-Gebäuden wie Diners oder Grocery Stores, die mit futuristisch-extravaganten Formen und lauten Neonlichtern an der Straße stehen und nun Stück für Stück abgewickelt werden, weil sie zu teuer im Unterhalt sind. Dass Konsum nicht mehr so unterhaltsam ist, wie er mal war, trifft nun eine der fröhlichsten Verkörperungen eben dieser Vorstellung.

Interessant finde ich den historisch-medialen Vergleich, den Anna Kodé aufmacht. Das Äquivalent zu den Smartphone-Screens von heute war, so die Überlegung, in der amerikanischen Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts die Scheibe des eigenen Autos. Und was man im Vorüberfahren sieht, die Landschaft mit ihren Straßen, Menschen und Bauten, ist der Content. Die Unternehmen buhlen darin mit ihren Bauwerken um die Aufmerksamkeit der motorisierten Kundschaft.

Just as today’s brands are built to shine on Instagram and TikTok, Googie structures were built to entice through a car window. They were usually at prominent intersections, and along with the neon signs, they had large glass windows “to show off the interior to people as they drove by,” Mr. Hess said. “People would look in and see a lot of happy diners. The whole building was a three-dimensional billboard displaying the color and the activity and the people.

Das Fenster als Bildschirm – eine klassische, in diesem Fall wörtliche und charmante Metapher. Die Welt als Bühne, die aus dem sicheren Zuschauerraum des Fahrzeugs betracht wird und zugleich die Möglichkeit bietet, betreten werden zu können. Konsum als Theaterstück, das man beobachten oder spielen kann.

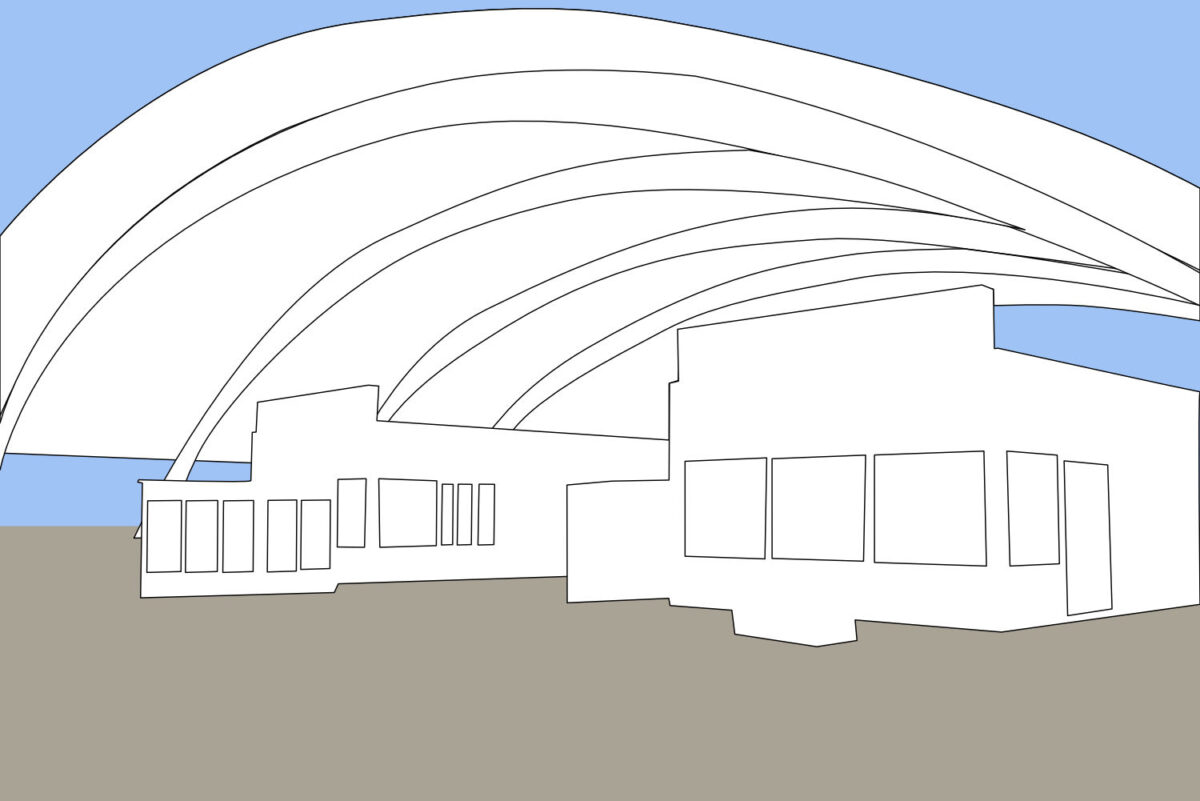

Visuell, aus der konkreten Sicht der Beobachtenden, berühren und verbinden diese Diners, Motels und Grocery Stores – wie jedes Gebäude – den Boden und die Erde. Sie sind jedoch explizit darauf angelegt, möglichst auffällige Formen, Farben und Signale in die Glätte des Himmels zu werfen. Darin liegt ihre unwahrscheinliche, verschwenderische Schönheit, die die Kundschaft anlocken soll.

So entfaltet sich eine mehrstufige Erfahrung für die Kund:innen: die erste ist die besagte Sicht aus dem Auto – vor dem Himmel zeichnet sich der Umriss einer leuchtenden, gut gelaunten Wirrnis ab. Stufe zwei besteht aus den Flächen und Lichtern, die sich innerhalb dieses Umrisses abzeichnen, sie weisen auf den Content innerhalb der Struktur hin. Stufe drei ist schließlich der Raum, der sich hinter den Fenstern (nun: der Läden) öffnet, mit Einrichtung, Konsument:innen und Waren.

Denkt man an die Flatness gegenwärtiger Bildschirme, übt dieses Changieren zwischen Zwei- und Dreidimensionalität, die Staffelung der Ebenen einen besonderen Reiz aus. Die Nostalgie, die diese Architektur verströmt, verdankt sich nicht (nur) der Historizität eines bestimmten baulichen Stils und noch weniger einer Sehnsucht nach den »guten alten Zeiten«. Es ist vielmehr die besondere Faltung, das Licht und die großzügige Gestik dieser Bauten, die bewegten Körpern und wandernden Augen eine einzigartige Landschaft schaffen. Auch abseits konsumatorischer Versprechungen und sozialer Kodierungen handelt es sich schlichtweg um ein Fest für die visuelle Wahrnehmung.